You have many reasons to link to different files representing the exact same song in a music catalog:

- You don’t want to hear it multiple times in a short amount of time

- You want to find one song when looking for it, not a collection of the same song

- You want to gather the related metadata for that same song (different languages, detailed artists…)

- You want to know the actual number of different songs in the catalog, with no duplicates

- You want to know who listened to song X, and not file X, file Y and file Z of the same song

- …

ISRC

For a long time, the ISRC has been seen as the ideal candidate to join these tracks. ISRC means International Standard Recording Code and is an international standard code for uniquely identifying sound recordings and music video recordings. In theory, this could fit for all cases. In practice, however, ISRC codes look somewhat random. An international music label may use different ISRC according to the country they are distributing it (they should not) ; a reedition, which is not a mastering, would be considered by some as an artistic change suggesting a new ISRC whereas other would use the same for a major change in the reedition ; some labels don’t want to pay the national institution which gives the ISRC codes and invent codes ; and others are making mistakes…

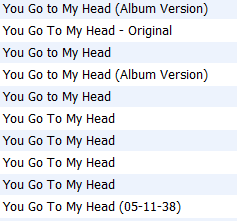

At the end, the exact same song end up having a wild range of ISRC:

This especially happens on public domain popular songs, heavilly reedited by many labels worldwide, such as the above “You Go to My Heart”, a jazz standard here sang by Billie Holiday.

Medatada

Other fields such as the song title, the artist names or the duration could be used to link tracks together. But again, although they should all look alike, many variations occur:

- Artists can be described very differently from one track to another (Artist A & Artist B as one single artist or separately, group members detailed…)

- The duration may not be equal even if the signal is actually the same because of added leading or tailing silence (exact duration can easily be found from signal analysis)

- Title could be written in many different ways, on purpose (more details), by mistake (wrong spelling) or depending on the local language (specifically for classical music where “songs” have translatable titles). On the last figure you could see “You Go to My Heart” and “You Go to My Head“. Obviously one of the two spelling is wrong. Here is another example:

Besides, two songs may have very similar metadata without beeing the same at all. Think of songs such as “I love you”, “Piano sonata”, …

All this makes the track comparison by metadata extremely difficult and time consuming, especially on a multi million track database. Choosing which title fits best can be obvious for a human brain, but not for a machine.

Fingerprint

As Deezer goes on, track fingerprinting is becoming a useful tool to handle this issue. Computing a track fingerprint and comparing their result is not only easier, but also a lot more reliable. Fingerprinting is being used by many companies such as Spotify and The Echo Nest. The idea is to forget ISRC and other metadata alltogether, and compare audio files together with what matters most: the signal.

Fingerprint comparison on a catalog can lead to:

- Detecting bad metadata, if a few stands from a majority

- Enrich metadata by propagating them to all the tracks with the same fingerprint

- Reduce disk space by keeping only one version of the file

- Suggest tracks in a radio that has not been already played

- Group tracks together in a search result

- …

And all this with a high level of reliability. Fingerprinting is one of the best steps to overcome a wide amount of unreliable metadata and a smart alternative to ISRC comparison.